When I was a child, the California Condor made me cry.

Not due to physical trauma, mind you. I wouldn’t have stood a chance against a bird that stood nearly as tall as my five-year-old self.

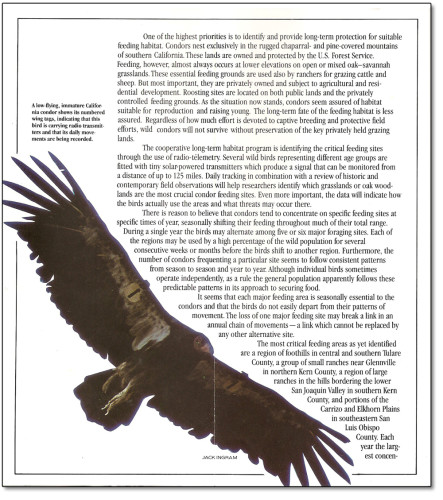

It reflected emotional pain. I loved birds and, when I learned the plight of the near-extinct species, I was heartbroken. The fact of losing a once-widespread icon of the western frontier was probably lost on me. It had a nine-foot wingspan – one of the largest of terrestrial birds worldwide – and I selfishly wanted to see one in the wild.

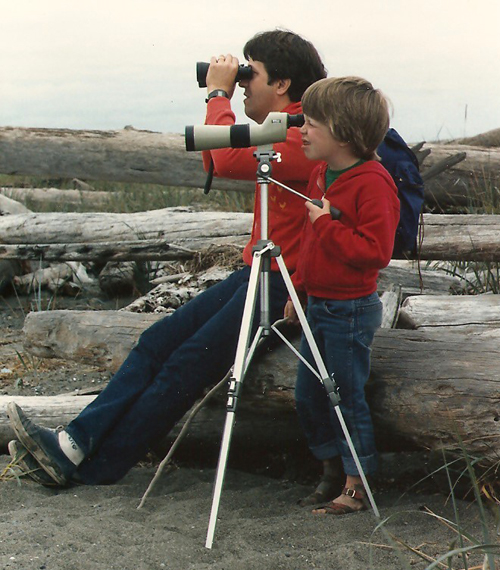

I was at a National Audubon Society conference with my mom who then worked at the Seattle chapter. The setting was magical: Asilomar on the California Coast near Monterey. A convivial flock of Acorn Woodpeckers on the premises is what attracted me to birdwatching: my “gateway bird,” so to speak.

Passionate bird conservationists gathered from around the country and, amongst the meetings and networking events, the California Condor took center stage. For the children, educators rolled out an impressive piece of cloth that was cut to represent the life-sized silhouette of the massive bird. Scientists gave presentations that outlined the plight of the species. At that time, in the mid-1980’s, there were only 22 birds left in the wild: the situation was dire. Habitat loss, the pesticide DDT, electrocution from power lines, pressures from cattle ranching and poisoning from lead shot proved too much for the dedicated scavenger.

I cried all night. According to my mother, I was inconsolable.

Word of my concern spread and, by the following morning, the world’s experts on California Condors had assembled at our breakfast table; PhD ornithologists had gathered to assuage the concerns of a five-year-old child. My mother recollects that I didn’t say a word, I just held my chin barely above the edge of the table. Undeterred by my melancholic state, the scientists reassured me that they were doing absolutely everything they could to save the emblematic species.

Unfortunately, I never did see a California Condor in the wild: the last one – a stubborn male called “AC9” – was dramatically caught by scientists in 1987 in a last ditch effort to rebuild the population through an ambitious captive breeding program. All of the California Condors in the world were contained in a facility at the San Diego Wild Animal Park and the Los Angeles Zoo (and later, facilities in Oregon and Idaho). Exposure to humans was strictly controlled: the locations were closed to the public and chicks were hand-reared with life-like condor sock puppets.

It worked. Fast forward thirty years and over 200 condors now form wild populations throughout central and southern California, northern Arizona, and Baja California (with another 200 birds in captivity). In 2003, chicks fledged in the wild for the first time in over two decades (over 40 birds have fledged in the wild through 2014, source).

When my wife and I discussed moving away from our native Seattle, we considered both San Francisco and New York City. As a birder, I mentally calculated that I could see more new species in the Northeast; San Francisco and Seattle are both on the west coast and, as a result, share many of the same birds. But California has condors; Washington and New York do not.

When we ended up moving to the Bay Area (a decision made totally independent of my birding life list) it started to look like I’d finally see a condor in the wild. And, for my 36th birthday, my wife suggested that we give it a shot; Highway 101 along the coastline of Big Sur National Park – a decent spot for spotting soaring condors – was only a 3.5 hour drive south.

The timing of our attempt, the Saturday after my birthday, was significant because it was also the birthday of my non-birding wife. She generously chose to spend the day searching for an obscure bird I’d revered since childhood.

Thankfully, the Big Sur coastline is some of the most beautiful landscape in the world. Mature redwood forests tucked into valleys flanked by curvaceous ridges of verdant pastures, all giving way to a undulating rocky coastline that creates endless points and bays in both directions. We stopped many times to scope the water: within minutes we saw the spout of a gray whale. Then another. And another. Soon, we watched a pod of hundreds of Common Dolphins gradually move north in the brilliant morning light.

At every stop, we found more cetaceans, mostly Gray Whales (migrating north from their breeding waters in Baja), pods of Pacific White-sided Dolphins, and a single Humpback Whale. Kristi used the spotting scope to watch the water while I scanned the ridge lines for soaring raptors. Nothing but Red-tailed Hawks, Common Ravens, and Turkey Vultures so far.

Our most productive spot was a nondescript pullout nicknamed “Sea Lion Lookout.” A group of four feeding Gray Whales allowed for sustained scope views, much to the delight of the many people who stopped to see what we were looking at. This was a good spot for condors so, as everyone looked out, I looked up, waiting for the silhouette that never showed.

We had plenty of coastline left so we continued to the popular Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park. It was a madhouse. Parked cars were overflowing onto the busy highway, so we decided to skip seeing the famous waterfall that everyone was there to see. As Kristi used the facilities before we returned to our car, I looked up yet again. After seeing nothing but hawks, vultures, and ravens, their massive wingspan was unmistakable, even to the naked eye. I scurried to get my binoculars to my eyes: the patches of white feathers extending down the inside of their wing was diagnostic.

California Condors.

As people and cars nonchalantly passed, I set up my scope and enjoyed prolonged views of four condors soaring along the ridge: one adult, with a bright orange head set against a crisp black and white underwing, and three darker, drabber juveniles. Kristi came out long enough for a brief look and a kiss on the cheek—a tradition whenever I see a new species.

Despite the fact that these birds were likely hatched in captivity and released into the wild (you can look up their birth date if you get a good enough view of the color and number of the wing tags, which I didn’t) they were riding wild thermals like they did centuries ago. The birdwatching purist in me appreciated the fact that the status of condors was recently reinstated as “countable” by the American Birding Association, the grand arbiter of what species are established in North America. This validated today’s sighting amongst my birdwatching peers. But that didn’t matter to the five-year-old who saw the wingspan unfurled in front of him three decades ago: he was thrilled.

“Whoa, what’s that!” Kristi broke my daydream a little further down the highway.

Another eight condors were soaring above the ridge line, this time much closer to the road. We quickly pulled off and I watched them for fifteen minutes before they all disappeared. We were in the right place and precisely the right time. It was a fleeting moment, but it’ll stay with me forever.

I wish I could thank the scientists who made it possible to see twelve California Condors in a single day. Over breakfast, of course.