It all started with a simple question: How many species have I seen while running? I’m relatively list adverse compared to other birders; state, county and yard lists are common examples, but, more obscurely, I’ve heard of a “C List,” or the number of species a birder has seen copulate. For me, I only keep lists for US/Canada — known among birders as an “ABA” list — and a world list, the latter of which is haphazardly scribbled throughout field guides and pads of aging paper. That’s all to say that I’m not inclined to keep lists, nor am I very good at it.

But with a toddler and two time-consuming hobbies, the idea of combining birding and running into one pursuit intrigued me.

Plus, it appeared novel—I hadn’t heard of anyone else attempting something like this before.

After the 12 month “Big Year” (a term I use very loosely) I maintained my normal “3 runs a week” schedule, tallying 138 individual runs. While birds influenced the destination of every single run, except for the last run of the year on December 31, I didn’t drive anywhere to specifically target birds. I ran from whenever I slept. Most frequently this was Washington D.C (81% of all runs left from our apartment near Chinatown).

In addition, I ran wherever we traveled and thankfully this included some interesting areas:

- Seattle-area, WA (13 runs)

- Arlington, VA (7 runs)

- San Francisco-area, CA (4 runs)

- Phoenix, AZ (1 run)

- Bethany Beach, DE (1 run)

I never used optics, more out of practicality instead of principles—they are heavy. Consequently, many duck silhouettes bobbing on the water and warbler butts went unidentified. I included “heard only” birds and considering my nascent familiarity with Eastern birds, this meant I missed a few more birds, especially during spring migration.

If I could sum up the effort in two words, it’d be “so close.” I ran 984 miles and saw or heard 197 species. This is much better than the 100 species I suspected, but I was so close to doubling my arbitrary goal.

Which species did I record the most? This list reflects my largely urban running environment:

- European Starling (90% of runs)

- Rock Pigeon (84% of runs)

- American Robin (84% of runs)

- House Sparrow (84% of runs)

- Mallard (72% of runs)

- Blue Jay (65% of runs)

- Canada Goose (61% of runs)

- Fish Crow (60% of runs)

- Ring-billed Gull (59% of runs)

- Song Sparrow (58% of runs)

- Common Grackle (57% of runs)

Of the 197 species I saw or heard this year while running, 28% I recorded only once and more than half (58%) I recorded on 5 or fewer runs.

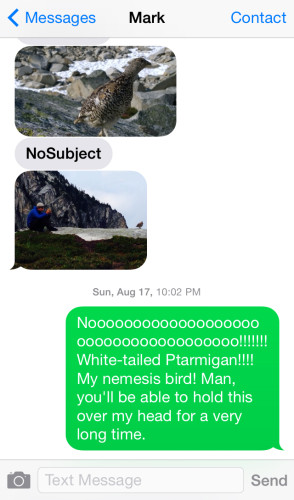

Which species did I totally miss this year? There are more than a few species that I somehow couldn’t find in 2018 while running, but the rare Black-headed Gull that was frequenting the Georgetown waterfront for a couple months probably stings the most. Including “out and backs,” I probably made nearly 20 attempts to see this stupid bird. People were feeding it bread, for crying out loud. It was most frequently reported in the afternoon and I prefer to run in the morning. Looking back, I should have changed my strategy.

Other surprising misses include Peregrine Falcon and Ruby-throated Hummingbird in D.C., Marsh Wren and Eurasian Collared-Dove out west. Cackling Goose and Sharp-shinned Hawk also stand out. I ran 14 miles on one run for a failed attempt at Long-tailed Duck near Georgetown and, back near Seattle, 16 miles to *not* find a Brandt’s Cormorant. A couple runs to a supposed Mississippi Kite nest site was also fruitless (the nest apparently failed).

But let’s not dwell on the negative. Here are some highlights:

January — I ended the month with 48 species and a partially hurt foot. The most exciting bird was the reddish wings and gray collar of a SWAMP SPARROW at Theodore Roosevelt Island, what will become a frequent destination this year.

February — The January foot issue crept into February and, not wanting to impact an expensive ski vacation, I took two weeks off from running—not the strongest start to the year. I ran 37 miles in the latter half of February and tallied six new species, including GREAT BLACK-BACKED GULL and ORANGE-CROWNED WARBLER.

March — I crawled back to my “3 run a week” schedule and with that increased mileage came new species, including a rare LARK SPARROW in the National Arboretum and a flock of RUSTY BLACKBIRDS—my second sighting ever (with or without running shoes). I also ran the Rock & Roll Half Marathon and added a COMMON RAVEN.

April — Spring Migration is starting and the action is picking up! I missed a rare Great Cormorant reported the previous day at Fletcher’s Cove but added six new species, including HAIRY WOODPECKER and BLACK VULTURE. I tallied SPOTTED SANDPIPER and GREEN HERON at Roosevelt Island but missed the Bonaparte’s Gulls reported just offshore. I ran 80 miles and added 25 more species.

May — Spring Migration treated me well, as expected. If the scads of warblers, grosbeaks, orioles and flycatchers in D.C. weren’t enough, I also took advantage of a bachelor party in arid Scottsdale, AZ. Perhaps I was not in peak aerobic fitness on the final morning of our trip, but I tallied 14 desert species, including HARRIS’S HAWK. All told, I tallied 37 new species in May.

June — Spring migration was a tough act to follow, but a half marathon to Kenilworth Park added WHITE-EYED and WARBLING VIREOS and INDIGO BUNTING. I also learned about a small PURPLE MARTIN colony breeding behind the Georgetown Hospital.

July — I took two weeks off of running to go on a European road trip but returned to D.C. to hear a singing FIELD SPARROW and – after three attempts – found a COOPER’S HAWK across the street from Union Station.

August — This could’ve been a dry month, but four runs near San Francisco afforded me a staggering 23 new species for the year, include West Coast specialties like WRENTIT, RIDGWAY’S RAIL, NUTTALL’S WOODPECKER, PYGMY NUTHATCH and – a personal highlight – foraging WHITE-TAILED KITES.

September — This was the month where I attempted to find Ruby-throated Hummingbird and Black-headed Gull and struck out on both, many times. I did tally 4 new species on one run in coastal Delaware, including BROWN-HEADED and RED-BREASTED NUTHATCHES thus completing the coveted quadfecta of North American nuthatches.

October — I added a YELLOW-BELLIED SAPSUCKER in D.C. and on one run back near Seattle – my first since January – I tallied SNOW GOOSE, BARROW’S GOLDENEYE, DUNLIN and BROWN CREEPER.

November — On my second run near Seattle, I tweaked my ankle looking in a flock of American Wigeons for a Eurasian. Then I caught a head cold. After a 9-day hiatus, I returned to running in D.C. to find HERMIT THRUSH, AMERICAN KESTREL and LESSER BLACK-BACKED GULL.

December — I was sitting at 179 species and 862 miles with 31 days left in this year-long challenge. Two hundred species and a thousand miles were so close, but it would require a very strong, if not stupidly ambitious finish. We were already planning to spend over two weeks in the Seattle-area, where I had the potential to see quite a few new species. I just needed some luck and injury-free knees. Thankfully, I stayed healthy and hit 122 miles – the highest mileage this year – including 35 miles in the last four days. And the birds didn’t disappoint either: VARIED THRUSH, EURASIAN WIGEON, RHINOCEROS AUKLET and EARED GREBE were the highlights of the 18 species I added in December. I tried to go out with a bang as well, running 14 miles on the last day of the year and scoring two dandies: HARLEQUIN DUCK and BLACK TURNSTONE.

I’m taking the first week of January off running before I resume my normal running schedule. I’m also creating a new version of my “ABA Running List” spreadsheet … just in case.

2018 “RUNNING LIST” – By the Numbers

Number of runs: 138

Total Mileage: 984 miles

Total Species: 197

Average Mileage: 7.1 miles per run

Snow Goose

Canada Goose

Wood Duck

Northern Shoveler

Gadwall

Eurasian Wigeon

American Wigeon

Mallard

Ring-necked Duck

Lesser Scaup

Harlequin Duck

Surf Scoter

White-winged Scoter

Bufflehead

Common Goldeneye

Barrow’s Goldeneye

Hooded Merganser

Common Merganser

Red-breasted Merganser

Ruddy Duck

Gambel’s Quail

Pied-billed Grebe

Horned Grebe

Red-necked Grebe

Eared Grebe

Rock Pigeon

Band-tailed Pigeon

White-winged Dove

Mourning Dove

Chimney Swift

Anna’s Hummingbird

Ridgway’s Rail

American Coot

Black-necked Stilt

American Avocet

Killdeer

Long-billed Curlew

Black Turnstone

Sanderling

Dunlin

Long-billed Dowitcher

Spotted Sandpiper

Greater Yellowlegs

Pigeon Guillemot

Rhinoceros Auklet

Laughing Gull

Mew Gull

Ring-billed Gull

Western Gull

California Gull

Herring Gull

Lesser Black-backed Gull

Glaucous-winged Gull

Great Black-backed Gull

Caspian Tern

Common Loon

Double-crested Cormorant

Pelagic Cormorant

Great Blue Heron

Great Egret

Green Heron

Black-crowned Night-Heron

Black Vulture

Turkey Vulture

Osprey

White-tailed Kite

Bald Eagle

Cooper’s Hawk

Harris’s Hawk

Red-shouldered Hawk

Red-tailed Hawk

Belted Kingfisher

Acorn Woodpecker

Gila Woodpecker

Red-bellied Woodpecker

Yellow-bellied Sapsucker

Red-breasted Sapsucker

Nuttall’s Woodpecker

Downy Woodpecker

Hairy Woodpecker

Northern Flicker

Pileated Woodpecker

American Kestrel

Merlin

Eastern Wood-Pewee

Acadian Flycatcher

Willow Flycatcher

Black Phoebe

Eastern Phoebe

Ash-throated Flycatcher

Great Crested Flycatcher

Western Kingbird

Eastern Kingbird

White-eyed Vireo

Hutton’s Vireo

Blue-headed Vireo

Warbling Vireo

Red-eyed Vireo

Steller’s Jay

Blue Jay

California Scrub-Jay

American Crow

Fish Crow

Common Raven

Purple Martin

Tree Swallow

Violet-green Swallow

Northern Rough-winged Swallow

Cliff Swallow

Barn Swallow

Carolina Chickadee

Black-capped Chickadee

Chestnut-backed Chickadee

Oak Titmouse

Tufted Titmouse

Verdin

Bushtit

Red-breasted Nuthatch

White-breasted Nuthatch

Pygmy Nuthatch

Brown-headed Nuthatch

Brown Creeper

House Wren

Pacific Wren

Winter Wren

Carolina Wren

Bewick’s Wren

Cactus Wren

Blue-gray Gnatcatcher

Golden-crowned Kinglet

Ruby-crowned Kinglet

Wrentit

Eastern Bluebird

Western Bluebird

Swainson’s Thrush

Hermit Thrush

Wood Thrush

American Robin

Varied Thrush

Gray Catbird

Curve-billed Thrasher

Brown Thrasher

Northern Mockingbird

European Starling

Cedar Waxwing

Phainopepla

House Sparrow

House Finch

Pine Siskin

Lesser Goldfinch

American Goldfinch

Spotted Towhee

Eastern Towhee

Canyon Towhee

California Towhee

Chipping Sparrow

Field Sparrow

Lark Sparrow

Black-throated Sparrow

Fox Sparrow

Song Sparrow

Swamp Sparrow

White-throated Sparrow

White-crowned Sparrow

Golden-crowned Sparrow

Dark-eyed Junco

Orchard Oriole

Hooded Oriole

Baltimore Oriole

Red-winged Blackbird

Brown-headed Cowbird

Rusty Blackbird

Common Grackle

Great-tailed Grackle

Ovenbird

Northern Waterthrush

Black-and-white Warbler

Orange-crowned Warbler

Lucy’s Warbler

Common Yellowthroat

American Redstart

Cape May Warbler

Northern Parula

Magnolia Warbler

Bay-breasted Warbler

Blackburnian Warbler

Yellow Warbler

Blackpoll Warbler

Black-throated Blue Warbler

Palm Warbler

Pine Warbler

Yellow-rumped Warbler

Prairie Warbler

Northern Cardinal

Rose-breasted Grosbeak

Blue Grosbeak

Indigo Bunting