Read all posts from this expedition to South Korea

“It’s just to the left of that red ramen container.”

I found the piece of trash on the beach with my spotting scope and scanned left: got it. The beautiful russet tones and yellow legs of a juvenile Sharp-tailed Sandpiper shone brilliantly through the huddled mass of brown shorebirds, mostly Red-necked Stints, Kentish (Snowy) Plovers, and Dunlin. This sandy island, nestled in the Nakdong Estuary near Busan (the second largest city in South Korea), was important habitat for Siberian breeding shorebirds en route to wintering grounds as far south as Australia.

But I wasn’t here to look at Sharp-tailed Sandpipers, red ramen containers, or any other piece of urban detritus—ranging from construction cones to an old refrigerator—that littered this one mile stretch of wind beaten sand and tidal flats. I’d accompanied Gerrit Vyn from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, and four members of the non-profit Birds Korea, to record migrating Spoon-billed Sandpipers.

Spoon-billed Sandpipers, or “spoonies” to anyone lucky enough to frequently speak of the species, are one of the rarest birds in the world—about a hundred pairs remain.

Unfortunately, tidal flats in the Yellow Sea are becoming nearly as rare. Over 75% of South Korea’s historical tidal flats have been “reclaimed” to support an exploding population and a bustling economy, with at least half of this conversion occurring in the last 20 years.

Turning bustling communities from mud may seem like an improvement to most, but migrating shorebirds require these stops to refuel enough for the next leg of their annual journey. It’s like using three tanks to drive to Grandma’s house every Thanksgiving: not a problem when there are a couple gas stations along the way that you’ve stopped at for generations. But take away even one of those refueling locations and your entire journey is in jeopardy.

The dedicated volunteers of Birds Korea have dedicated themselves to fending off development to protect the few Korean mudflats that remain, using the Spoon-billed Sandpiper as its rallying cry. Cornell’s Gerrit Vyn was in South Korea to highlight the ecological importance of the Yellow Sea on this migratory shorebird pathway, hoping to gather high-definition video that would complement footage he’d already gathered on their wintering grounds in Myanmar (Burma) and breeding territory in Siberia—the first of its kind.

We’d only been in South Korea for two days and we had yet to see a “spoonie.” With a population in the low hundreds, we knew it’d be hard to find even one in the hundreds of thousands of shorebirds that migrate down the Korean Peninsula. But Dr. Nial Moores—Director of Birds Korea—had found two juveniles at this location the week prior to our arrival, and he had a distant sighting yesterday evening as he was scoping an adjacent mudflat.

During our second morning, we’d found a large flock of several thousand shorebirds that had settled near the water’s edge at high tide. Jason Loghry, an American expat and Birds Korea volunteer, and I approached the flock carefully with our scopes while Dr. Moores moved in from our right. Gerrit Vyn was slowly approaching the same flock on his stomach, sliding his camera on a modified dish “tripod” in front of him. The flock of Red-necked Stint, Sanderling, Dunlin, Kentish Plover (known as Snowy Plover to North Americans), Lesser Sand-Plover, and Sharp-tailed Sandpipers were all resting while they waited to resume feeding once the mudflats were exposed on the outgoing tide. We knew there was likely a Spoon-billed Sandpiper in the mix but, as shorebirds frequently do while they are resting, that diagnostic spoon-shaped bill—unique amongst the world’s sandpipers—was tucked under one of these grayish brown wings.

Jason took a quiet call on his cell phone. He hung up and whispered to me, “Dr. Moores just saw a spoonie!”

It was somewhere in the same flock we were scanning. It had woke up long enough to expose its distinctive bill and was somewhere near one of the two black trash bags (not near the ramen container, old hat, or moldy shoe). We scanned intently for ten minutes. Nothing: it may only be viewable from his angle. Hopefully Gerrit, who was within feet of the resting birds, was having better luck.

As the tide receded, the flock grew increasingly restless. Finally, a Eurasian Hobby—a small falcon that feeds on shorebirds—caused every bird to flush to the air. As Gerrit got to his feet and came back to our group, it was clear that Dr. Moores was the only person to the see the “spoonie.” As the tide dropped, and the mudflats—and survey area—increased in size, the likelihood that we’d get close enough for reasonable footage (let alone find the bird), decreased dramatically. While Gerrit had captured some stunning footage of some of the other birds, this was our second failed attempt at finding our target species.

We decided to walk the kilometer back to the other side of the island (where we had dropped our bags after the boat had dropped us off) to grab lunch. On the way, I had fleeting glimpses of a small flock of calling passerines with dark tails and white outer tail feathers. Dr. Moores confirmed they were Richard’s Pipits, a lifer for me. I also had the chance to study Far Eastern Curlews, another lifer and the largest shorebird in the world, on a mudflat across the channel.

As we arrived back at our de facto base camp, over forty people stormed the beach from five separate boats. Dr. Moores stated that this crew comes to the island daily to help remove the trash. He is quick to dismiss their presence as nothing more than a misguided economic stimulus scheme, an effort by the local government to employ both the workers as well as the boat owners who take them from to and from this inaccessible island every day. When you consider that the island still hosts one of the most littered beaches I’ve ever seen, as well as the fact that their small tent city actually requires them to bring more trash to the island, it’s hard to support their efforts.

We nodded and smiled as this day-glo army walked by our base camp to the shade of their tarp and bamboo huts, and broke open the bags of rice balls and snack foods purchased from a convenience store that morning.

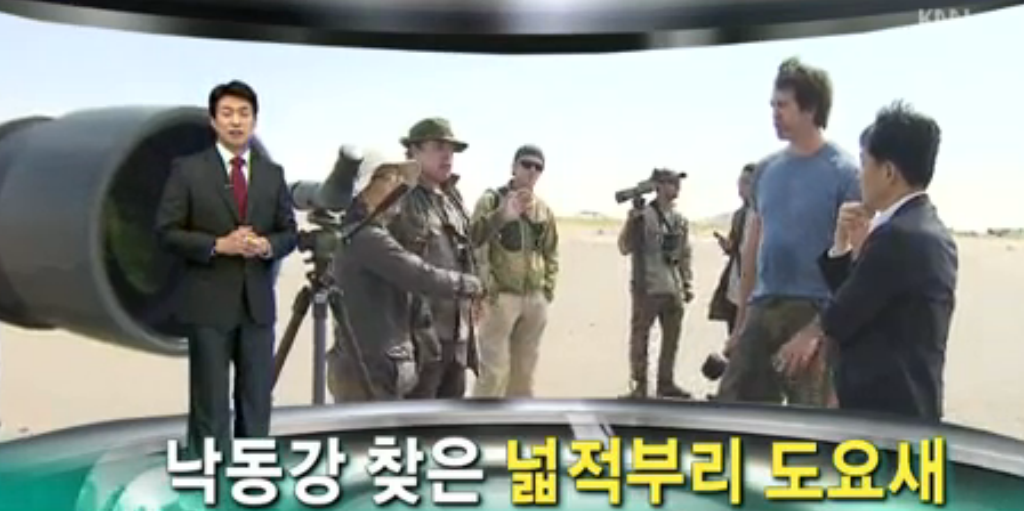

Within minutes, another boat arrived carrying a TV cameraman, his smartly-dressed assistant, and the journalist donning a suit jacket and wide-brimmed straw hat. Our friends at Birds Korea had asked Chin Jae-Un, director of an award-winning documentary about the migration of Bar-tailed Godwits and local news anchor, to visit the team in situ on the island. They posed questions to the team, and staged footage of Gerrit crawling over the sand towards a fictitious Spoon-billed Sandpiper with the rest of the team using our optics to search for the same. The special report, featuring the first television broadcast of Gerrit’s footage from Siberia, aired that evening (watch it here).

After leaving the island early so Gerrit could share high-resolution video with the Korean news team, we visited nearby Myeongji, a city that has recently sprung up from reclaimed tidal mudflats in the Nakdong Estuary. The rigid, rectangular profile of this new peninsula stands in stark contrast to the undulating, pulsating shoreline that it replaced. The construction cranes looming over the new apartment complexes mirrored a similar stretch of cranes on the adjacent shoreline, which stood ominously in front of the setting sun.

Hundreds of Spot-billed Ducks, as well as a small flock of Taiga Bean-Geese and a pair of Swan Geese (both lifers) could be found in the remaining wetlands, viewable from the long bike path that tops the long, straight sides of this fortified shoreline.

Gerrit had gathered valuable footage to capture the pressures that the Yellow Sea ecosystem must endure. But we’d have to wait another twenty-four hours, and drive over 150 miles, before our first glimpse of a Spoon-billed Sandpiper.

Ha! I hadn’t even thought of that. Too bad I couldn’t find any Red-breasted Geese (apparently the first record for Korea was just last winter). https://flockingsomewhere.com/wild-goose-chase/

Still on a wild goose chase, eh, Adam? Taiga Bean-Geese and Swan Geese!? Cool! And thanks for sharing your travels!

Thank you for the reminder! I fixed it. And thank you for checking out my post!

Great write-up of your trip. Looking forward to more.

There seems to not be a link to the television footage you mention.